Introduction

Last updated on 2023-09-07 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Overview

Questions

- “What kinds of diseases can be observed in chest X-rays?”

- “What is pleural effusion?”

Objectives

- “Gain awareness of the NIH ChestX-ray dataset.”

- “Load a subset of labelled chest X-rays.”

Key Points

- “Algorithms can be used to detect disease in chest X-rays.”

Chest X-rays

Chest X-rays are frequently used in healthcare to view the heart, lungs, and bones of patients. On an X-ray, broadly speaking, bones appear white, soft tissue appears grey, and air appears black. The images can show details such as:

- Lung conditions, for example pneumonia, emphysema, or air in the space around the lung.

- Heart conditions, such as heart failure or heart valve problems.

- Bone conditions, such as rib or spine fractures

- Medical devices, such as pacemaker, defibrillators and catheters. X-rays are often taken to assess whether these devices are positioned correctly.

In recent years, organisations like the National Institutes of Health have released large collections of X-rays, labelled with common diseases. The goal is to stimulate the community to develop algorithms that might assist radiologists in making diagnoses, and to potentially discover other findings that may have been overlooked.

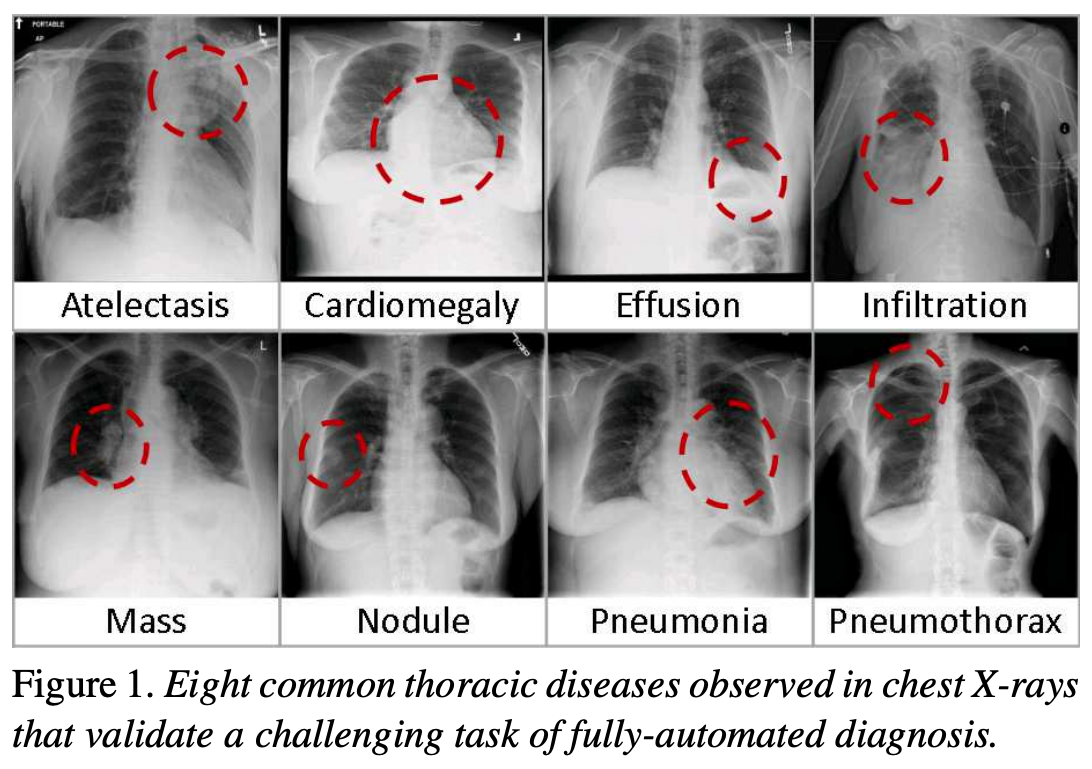

The following figure is from a study by Xiaosong Wang et al. It illustrates eight common diseases that the authors noted could be be detected and even spatially-located in front chest x-rays with the use of modern machine learning algorithms.

Pleural effusion

Thin membranes called “pleura” line the lungs and facilitate breathing. Normally there is a small amount of fluid present in the pleura, but certain conditions can cause excess build-up of fluid. This build-up is known as pleural effusion, sometimes referred to as “water on the lungs”.

Causes of pleural effusion vary widely, ranging from mild viral infections to serious conditions such as congestive heart failure and cancer. In an upright patient, fluid gathers in the lowest part of the chest, and this build up is visible to an expert.

For the remainder of this lesson, we will develop an algorithm to detect pleural effusion in chest X-rays. Specifically, using a set of chest X-rays labelled as either “normal” or “pleural effusion”, we will train a neural network to classify unseen chest X-rays into one of these classes.

Loading the dataset

The data that we are going to use for this project consists of 350 “normal” chest X-rays and 350 X-rays that are labelled as showing evidence pleural effusion. These X-rays are a subset of the public NIH ChestX-ray dataset.

Xiaosong Wang, Yifan Peng, Le Lu, Zhiyong Lu, Mohammadhadi Bagheri, Ronald Summers, ChestX-ray8: Hospital-scale Chest X-ray Database and Benchmarks on Weakly-Supervised Classification and Localization of Common Thorax Diseases, IEEE CVPR, pp. 3462-3471, 2017

Let’s begin by loading the dataset.

PYTHON

# The glob module finds all the pathnames matching a specified pattern

from glob import glob

import os

# If your dataset is compressed, unzip with:

# !unzip chest_xrays.zip

# Define folders containing images

data_path = os.path.join("chest_xrays")

effusion_path = os.path.join(data_path, "effusion", "*.png")

normal_path = os.path.join(data_path, "normal", "*.png")

# Create list of files

effusion_list = glob(effusion_path)

normal_list = glob(normal_path)

print('Number of cases with pleural effusion: ', len(effusion_list))

print('Number of normal cases: ', len(normal_list))OUTPUT

Number of cases with pleural effusion: 350

Number of normal cases: 350MATLAB

Introduction to the MATLAB GUI

Before we can start programming, we need to know a little about the MATLAB interface. Using the default setup, the MATLAB desktop contains several important sections:

- In the Command Window we can execute commands.

Commands are typed after the prompt

>>and are executed immediately after pressing Enter. - Alternatively, we can open the Editor, write our code and run it all at once. The advantage of this is that we can save our code and run it again in the same way at a later stage.

- The Workspace contains all the variables which we have loaded into memory.

- The Current Folder window shows files in the current directory, and we can change the current folder using this window.

-

Search Documentation on the top right of your

screen lets you search for functions. Suggestions for functions that

would do what you want to do will pop up. Clicking on them will open the

documentation. Another way to access the documentation is via the

helpcommand — we will return to this later.

Working with variables

In this lesson we will learn how to manipulate the inflammation dataset with MATLAB. But before we discuss how to deal with many data points, we will show how to store a single value on the computer.

We can create a new variable by

assigning a value to it using =:

OUTPUT

x =

55Notice that matlab responded by printing an output confirming that the variable has the desired value, and also that the variable appeared in the workspace.

A variable is just a name for a piece of data or value.

Variable names must begin with a letter, and are case sensitive. They

can contain also numbers or underscores. Examples of valid variable

names are weight, size3,

patient_name or alive_on_day_3.

The reason we work with variables is so that we can reuse them, or save them for later use. We can do operations with these variables. For example, we can do a simple sum:

OUTPUT

y =

10

ans =

65Note that the answer was saved in a new variable called

ans. This variable is temporary, and will be overwritten

with any new operation we do. For example, if we now substract y from x

we get:

OUTPUT

ans =

45The result of the sum is now gone forever. We can of course assign the result of an operation to a new variable, for example:

OUTPUT

z =

550This created a new variable z. If you look at the

workspace, you can see that the value of z is 550.

We can even use a variable in an operation, and save the value in the same variable. Fer example:

OUTPUT

y =

2Where you can see that the expression to the right of the

= sign is evaluated first, and the result is then

assigned to the variable specified to the left of the =

sign.

Of course, we can use multiple variables in a single operation, for example:

OUTPUT

z =

817where we used the caret symbol ^ to take the third power

of y.

Logical operations

In programming, there is another type of opperation that becomes very important: comparison. We can compare two numbers (or variables) to see which one is smaller, for example

OUTPUT

c1 =

logical

1Something interesting just happened with the variable c1. If I ask

you wether frac (8) is smaller than 10, you would say “yes”. Matlab

answered with a logical 1. If I ask you wether frac is

greater than 10, you would say “no”. Matlab answers with a

logical 0.

OUTPUT

c2 =

logical

0There are only two options (yes or no, true or false, 0 or 1), and so it is “cheaper” for the computer to only save space for those two options.

The “type” of data is not the same as a number. It comes froma logical comparison, and so matlab identifies it as such.

You can also see that in the workspace these variables have a tick next to them, instead of the squares we had seen. There is actually other symbols we can get there, which relate to the types of information we can save (unfold the info below if you want to know more).

Data types

We mentioned above that we can get other symbols in the workspace which relate to the types of information we can save.

We know we can save numbers, and logical values, but we can also save letters or strings, for example. Numbers are by default saved as type double, which just means they can store very big or very small numbers. Letters are type ‘char’, and words or sentences are “strings”. Logical values (or booleans) are values that mean true or false, and are represented with zero or one. They are usually the result of comparing things.

OUTPUT

weight =

64.5000

size3 =

'L'

patient_name =

"Jane Doe"

alive_on_day_3 =

logical

1Notice the single tick for character variables, in contrast with the double quote for strings.

If you look at the woorkspace, you’ll notice that the icon next to each variable is different, and if you hover over it, it will tell you the type of variable it is.

We can also check if two variables (or even operations) are the same

OUTPUT

c3 =

logical

1And we can combine comparisons. For example, we can check wether frac is smaller than 10 and the age is greater than 5

>> c4 = frac < 10 && age > 5

```matlab

```output

c4 =

logical

0In this case, both conditions need to be met for the result to be “yes” (1).

If we want a “yes” as long as at least one of the conditions are met, we woudl ask if frac is smaller than 10 or the age is greater than 5

OUTPUT

c5 =

logical

1Negating conditions and including the limits

We often asks questions or characterise things in negative. “We did not start late today.”, “I was not going faster than the speed limit officer!”, and “I didn’t shoot no deputy” are just some examples.

Naturally, we may want to do so in programming too. In matlab the

negative is represented with ~. For example, we can check

if the speed is indeed not faster than the limit with

~(speed > 70), which matlab reads as “not speed greater

than 70”.

Can you express these questions in matlab code? - Is 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 not smaller than 10? - Is 5 to the power of 3 different from 125? - Is x + y not greater or equal to x/y?

We can ask the first two question in positive, encapsulate it in

brackets, and then negate it: - ~(1 + 2 + 3 + 4 < 10) -

~(5^3 == 125)

Asking if two things are different is so common, that matlab has a

special symbol for it. So the second question, we could have asked

instead with - 5^3 ~= 125

- We can ask if x+y is greater or equal to x/y with

x+y > x/y || x+y == x/y, so asking if x + y not greater or equal to x/y we do by negating the above with brackets:~(x+y > x/y || x+y == x/y)

That last one seems a bit too complicated, and it is all beacuse we

need to include the limit, that is, because we want to include

values that are greater and equal to

something. There is actually a special symbol in matlab for that

>=, and of cours for smaller or equal too

<=.

Using this symbol, our last answer becomes

~(x+y >= x/y), which does not look nearly as scary.

Arrays

You may notice that all of the variable types start with a

1x1. This is because matlab thinks in terms of

groups of variables called arrays, or matrices.

We can create an array using square brackets and separating each value with a comma:

OUTPUT

A =

1 2 3If you now hover over the data type icon, you’ll find that it shows

1x3. This means that the array A has 1

row and 3

columns.

We can create matrices using semi-colons to separate rows:

OUTPUT

B =

1 2

3 4

5 6You’ll notice that B has three rows and two columns, which explains

the 3x2 we get from the workspace.

We can also create arrays of other types of data. For example, we could create an array of names:

OUTPUT

Names =

1×4 string array

"Jhon" "Abigail" "Bertrand" "Lucile"Or we can use logical values too:

OUTPUT

C =

4×1 logical array

1

0

0

1Something to bear in mind, however, is that all values in an array must be of the same type.

I mentioned before that matlab is actually used to working with arrays rather than individual variables. Well, if it is so used to them, can we do operations with them?

The answer is of course yes! In fact, this is what makes MATLAB a particularly interesting programming language.

We can, for example, check the whole matrix B and look for values greater than, say, 3.

OUTPUT

ans =

3×2 logical array

0 0

0 1

1 1Matlab then compared each element of B and asked “is this element greater than 3?”. The result is another array, of the same size and dimensions as B, with the answers.

We can also do sums, multiplications, and pretty much anything we want with an array, but we need to be careful with what we do.

Despite this being so interesting and increadibly powerful, this course will focus on more basic programming concepts, and so we will use the feature rather little. However, it is very important that you keep it in mind, and that you do ask questions about it during the break if you are interested.

Suppressing the output

In general, the output can be a bit redundant (or even annoying!), and it can make the code slower, so it is considered good form to always supress it. To supress it, we add a semi-colon at the end of the line:

At first glance nothing appears to have happened, but the workspace shows the new value was assigned.

Printing a variable’s value

If we really want to print the variable, then we can simply type its name and hit Enter,

OUTPUT

patient_name =

"Jane Doe"or using the disp

function.

Functions are pre-defined algorithms (chunks of code), that can be used multiple times. They usually take some “inputs” inside brackets, and either produce something or output something.

The disp function, in particular, takes just one input – the variable that you want to print – and what it does is to print the variable in a nice way. For the variable patient_name, we would use it like this:

OUTPUT

Jane DoeNote how the output is a bit different from what we got when we just typed the variable name. There is less indentation and less empty lines.

Keeping things tidy

We have declared a few variables now, and we might not be using all

of them. If we want to delete a variable we can do so by typing

clear and the name of the variable, e.g.:

You might be able to see it disappear from the workspace. If you now try to use alive_on_day_3, matlab will error.

We can also delete all our variables with the

command clear, without any variable names. Be careful

though, there’s no way back!

Another thing you might want to clear every once in a while is the

output. To do that, we use the command clc.

Again, there is no way back!

Key Points

- “Variables store data for future use. Their names must start with a letter, and can have underscores and numbers.”

- “We can add, substract, multiply, divide and potentiate numbers.”

- “We can also compare variables with

<,>,==,>=,<=,~=, and use~to negate the result.” - “MATLAB stores data in arrays. The data in an array has to be of the same type.”

- “You can supress output with

;, and print a variable withdisp.” - “Use

clearto delete variables, andclcto clear the console.”